Tag Archives: Arunachal Pradesh

Wakro – Back to School

On the Eastern Most Road of India – to Kaho and Kibithu

Half a century ago, India suffered its worst military attack, and subsequent defeat, throwing open a gaping hole at the border, and proving how unprepared India was, militarily and politically. On the 50th anniversary of the Chinese invasion, this post is dedicated to some of our bravest soldiers who fought, who died, and who went missing during Indo-China War, 1962.

*********************************************************************

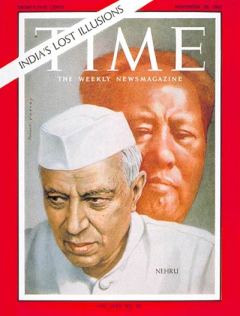

In November 1962, TIME magazine paid a tribute to the Indian soldiers who fought in the Indo-China War in Walong. It said, ‘At Walong, Indian troops lacked everything. The only thing they did not lack was guts’.

In October 1962, when the Chinese planned their incursion into the north-eastern sector inIndia, a region they would later call the “Tiger’s mouth”, they exposed the unready state of the Indian military. At the same time, what stood out was the heroic resistance of the Indian soldiers. The tragic bloodshed took place around the hills in Namti , near Walong, which has a special place in the history of India’s battles.From 22 October 1962 till the fall of Walong, on the 16th of November 1962, soldiers from the Sikh, Kumaoni, Gorkha and Dogra regiments fought a common enemy, shoulder-to-shoulder, in this unknown territorry. Ill-equipped and totally under prepared for such battles, some of the soldiers had to withdraw, crawling through the treacherous terrain. The rest of the soldiers never received any orders. Totally cut from their battalion, the soldiers fought it out to the last bullet, to the last man, till there was nothing left.

When the firing was over, and cease-fire declared, the army returned to the inhospitable terrain only to find that the Chinese had marked the positions of the dead. The Indian bunkers showed the dead where they had last manned their weapons. The Chinese had at least paid respect to their dead enemies – all the bodies were covered.

It is not uncommon to find the remains of the war, even now. Burnt pieces of army uniforms, fire arms, live ammunition, and other personal items lie scattered under rocks, tall grass and pine trees on the mountains.

In July 2010, the Border Road Task Force found a circular identity disc, PIS No. 3950976, and a silver ring, while clearing landslides in Walong. When the army checked the war records, they found that the disc belonged to Sepoy Karam Chand Katoch of the 4th Dogra Regiment. The local army unit then dug the area and found the remains of Karam Chand, along with a fountain pen, dilapidated pay book and a few ammunition. His mortal remains were flown to his home in Palampur, in Himachal Pradesh, from where, as a 19 year old soldier, he had left home to fight for his mother land. Before they flew his mortal remains, he was given a full honor salute at the War Memorial in Walong.How tragic that the selfless acts of bravery goes unknown to the majority of Indians?

The next morning, up early, we drove further east. The first stop, just outside Walong town and past the Army complex, was the memorial built by the Lohit Brigade to salute the brave and selfless sacrifices made by the Army men during the 1962 war. Known as the ‘Hut of Remembrance’, here the names of each of the martyrs who had laid down their lives in defence of the Lohit valley in 1962 is etched in marble.

We spent a few minutes walking around the black marble plaques, reading the names of the young soldiers who fought on the rugged mountain tops, suffering from extremes of cold, hunger and thirst, only to lay down their lives for our better tomorrow. It was a sombre moment for both of us.

The war memorial and epitaph that I mentioned in the previous post stands on the Namti Plains, by the Lohit River, to commemorate the exemplary sacrifice of our brave soldiers.

But before visiting the war memorial we had to take a detour to Tilam. Just 4 km out of town, Tilam is known for its hot springs that, reportedly, have medicinal properties. On the banks of the springs a brand new circuit house was getting readied. We parked in front of the circuit house and walked down to the springs. Though a bit dirty, the water was boiling hot.

We walked a bit further over a hanging bridge to where the climb up to Dong village begins. Overlooking Burma and China, this village has cornered the distinction of being the Indian habitation to catch the first rays of the sun. It’s a climb of an hour and a half hour which needs to be commenced at 3 in the morning, and not without a guide or a local.

It was in the turn of the last millennium when flocks of tourists swarmed to the hill top here to catch the first rays of the first sunrise of the 21st century light up the Dong valley and, in time, the rest of the country. We wanted to walk to ‘Millennium Point’ at Dong but we had to take permission from the Indian Army and without a permit no one could go.

Promising that we would take the walk to Dong the next time, we climbed back into our vehicle. Our next destination was Kaho. On the climb up to Kaho, there was little traffic. The Namti plains stretched before our eyes, pretty and pine laden. After a brief stop at the war memorial we proceeded further.

With every turn, the mountains on the Chinese side grew larger in view. The settings were so surreal. I was trying to imagine the place about 50 years back. A yellow board reminded us of being on the eastern most road in India.

We crossed a few metal bridges and were now driving along the Lohit River. Jayantoda mentioned that all these bridges had been replaced recently from the traditional ones. A ‘traditional’ one still hung precariously a bit further. We were standing in front of what the Mishmis call a ‘bridge’. In reality, it was just a lot of planks tied together that straddled both the banks of the Lohit. At that great height, the uncontrollable swing of the bridge and the turquoise water raging down below, a walk up to the other end and back needs some steely nerves. And I had to do it.

Mission accomplished, we drove into Kaho, a small village on the eastern most border, situated in a small valley surrounded by towering mountain peaks, most of them on the Chinese side. Kaho has around nine households. Cutting into the serenity of this small village is the constant presence of the Army all around and after all, the Line of Actual Control is not too far from here. Besides the village school, a monastery and a small tea shop cum PCO, Kaho is all about silence and the virgin beauty that the landscape offers.

We walked in to the Lohit Goodwill school and said hello to the children there. The teacher, apologetic about the poor attendance – the school had just reopened after Dushera – showed us into her class rooms. There were only four children, five were absent. The teacher herself had reached the previous night from Tezu, her home town, after the holidays.

From the school we walked up to the monastery only to realize that it was closed. A short climb up from the monastery is an Indian Army outpost and we paid them a courtesy visit. The two jawans at the look out were gracious enough to point out where the border lies and the various peaks on both sides and allowed us a quick peek through their binoculars at Chinese side.

“I can see a house with blue paint”, I said triumphantly. “Well, the Chinese can see the print on your dress, Madame”, one of the jawan said teasingly. “They have a binoculars powerful than ours and they are constantly monitoring the civilian traffic in our area. If they see more traffic, they get stressed out and if they get stressed out, it indirectly affects our sleep”. For civilians like us this journey is just a picture in an album, a page in a book. For the army its the whole volume.

On the way back, we drove up to Kibithu, currently the brigade HQ of the Indian Army.

Here civilian entry is monitored if not entirely restricted. We had to give our details at the check post. The helipad here used to be an attraction for the great views it offered. Presently, it is out of bounds for anyone who is not army and photography is not permitted.

We stopped for lunch in one of the small restaurants there. I never knew that the humble 2-minute Maggie could be so delicious.

There was one more place to visit before we drove back to our guest house. Equally touching and another must-see point in Walong is the Helmet Top, 18 kms by road above Walong. A patriotic pilgrimage of sorts that every Indian needs to take, Helmet Top was once a vantage point for the Indian army. During the war, a few of the Indian soldiers were stranded here. None of their counterparts back at the headquarters were aware of this. Exposed to the cold, suffering from hunger, thirst and frost bite, the soldiers were left to die. It is said that, after the battle was over, all that remained of the gallant Indian defenders were their helmets. Today, a memorial stands in a grim reminder of their courage and commitment.

Helmet Top [http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Helmet_Top_Walong_Memorial_Arunachal_Pradesh.jpg]

We must have covered around 15 km, and the white war memorial building was visible through the pine trees up above. But luck seemed to evade us. A big rock now lay in front of us blocking the whole road. We didn’t even try to move it, it was that huge. Jayantoda said if it had been a kilometer or so we could have tried walking to the top. But this was a risk. We were trying to find the positive side in it. What if the rock had fallen after we had passed that way? We would have had to spend the night at Helmet Top. Dejected, we decided to turn back.

On the way down we stopped at a small water fall and plucked a few wild oranges that could not have been more sour.

We decided to walk around the town before sun down. We met the same kids we had seen yesterday and they insisted on not only taking a few more photographs of them but also seeing the pictures we had taken yesterday. In return I was presented with a few wild flowers.

The sun was going down and this was our last night in Walong. When I closed my eyes, trying to sleep, along with the mountains and valleys that came rolling by, a small poem composed by a Walong veteran kept ringing in my ears.

- The sentinel hills that round us stand

- bear witness that we loved our land.

- Amidst shattered rocks and flaming pine

- we fought and died on Namti Plain.

- O Lohit gently by us glide

- pale stars above us softly shine

- as we sleep here in sun and rain.

We had to come back another time, for we had promised ourselves a sunrise at Dong and a prayer at Helmet Top.

With Uncle Moosa and friends in Tezu

It all began with our Uncle. Uncle Moosa we call him. Not just us. Most of East Arunachal calls him that – and for good measure.

It is Uncle, as part of a select band of social missionaries, who took a good part of two generations of the region on that delightful journey from A to B (and beyond!) And we are not even talking distances here. Which is what, usually, you would worry about when you think of a trip to Arunachal Pradesh.

Uncle quit a plush job in one of the most coveted of organizations – the Income Tax. While many were eager to land a job as an I.T.O., he quit it. That was not where his place was, he felt. Even as he did an M.A. in linguistics and bided his time there, bigger plans and a dream was preparing him for what he knew was his true calling.

One day he got the call. There was no caller ID those days. But he made out that it was from his inner self. He picked that, and a couple of bags, up and set out for that frontier where he saw the sun of his dreams rise. The destination was Arunachal Pradesh and the work cut out. Those were the early days of Vivekananda Kendra’s forays into lettering the North East and Uncle wanted to be a part of that movement. He, with a committed brethren of teachers and social activists, spent over 3 decades in the region – setting up schools, teaching and sculpting a future for generations.

32 years and thousands of students later, Sathyanarayanan Mundayoor a.k.a Unni a.k.a Uncle Moosa a.k.a Uncle Sir is pretty much an establishment himself. Only, now he has shed the Kendra’s banner and has donned another which hangs cheerfully outside his modest but neat library-cum-residence in Wakro, in Lohit district in eastern Arunachal– one of the thirteen small but purposeful reading rooms that he set up, almost single-handedly, in the remotest villages of the Lohit and Anjaw districts.

Uncle has a simple yet meaningful enough explanation of his move from the Kendra to starting the library movement in the state. This was, he said, a change from a big umbrella to a smaller umbrella. He felt his role in his earlier avatar had ended and that he just had to begin something new. To do that, he felt it was time for the smaller umbrella to unfold.

Lest he should tick us off for attributing the success of the library movement only to him, a quick clarification. It would also not have been possible but for the contributions – much needed funds, encouragement and physical volunteering – by his countless well-wishers all over Arunachal and the rest of India, and well the world. If one’s deeds were to be the measure of one’s stature, Uncle Moosa towers above most everyone we have met!

And it was Wakro, his present base, that we were eventually headed towards. There were still a few more places to be covered before that – Tezu, the many small villages along the Lohit; Walong and further up all the way to the Chinese border. These were more than lovely, lesser known places (which is what travellers like us seek them out for). For someone like Uncle, these were the outposts that needed all the support required to spread the light of learning and knowledge – places that his library movement had been blessed by. Each of these libraries had been set up by him (and, directly or indirectly, by his small but committed band of well-wishers, patrons and volunteers) in all those long, relentless trips made to these remote parts, carrying books and other material mostly by himself.

For anyone who thinks a trip to East Arunachal is easy, it is not. Unlike Tawang or Itanagar, this part of the state actually is not on travel agent itineraries. There aren’t even many options to stay…and certainly no hotels or resorts – something that, thankfully, we were not affected by. For, we had already got to sample some of the amazing social fare that Uncle has been instrumental in whipping up in East Arunachal. Our innerline permits, the logistics of our transportation, the social support we had en route to Pangsau…these otherwise formidable hurdles were, as if, never there. We are not sure how much Uncle realizes it, but for even someone as unstoppable and irrepressible as him, his reputation continues to precede him. And we were certainly not complaining! The warmth and affection with which we were received everywhere were ample proof of that – and we were more than happy to be the unwitting beneficiaries of that largesse.

We were back on the road again. Our “stroll down the Stilwell memory lane” and “the walk in the woods” in remote Namdapha brought us out via Bordumsa to the Mahadevpura border of Arunachal Pradesh, thanks to Jayanto da and his trusted Scorpio. A brief stop for lunch at a cross between a restaurant and a dhaba in Bordumsa was fulfilling.

Crossing the new bridge on the Lohit and passing the newer still the Golden Pagoda at Tengapani, we reached Chongkham. From the bridge, the monastery complex glistened in the evening sun.

At the crossroads, one road led to Wakro and Parasuramkund, the other towards the Pagla Ghat. As we were headed to meet Uncle in Tezu, we took the latter, enthused by the idea of the ferry crossing, with us and our vehicle in tow.

As with all ghat crossings, patience and luck are just as important as the ferry and the boatman! We were a little short of the former but were still blessed with some good fortune. A cool wind blew over the feisty Pagla Nadi (the mad river – named aptly so) and there weren’t too many people waiting to get across.

But it was a rare sight of the sun and the moon in the sky above that we were treated with. If the sunset on our left was blazing, the moon up above was a cool white.

The short cruise over the Pagla river was the stuff that indelible travel memories are made of. The sun was down but only just to cast a dull golden filigree over the wavy waters. Very few of us talked. Fewer still clicked pictures. That was not entirely surprising, given that this part of the state were, mercifully, not run over by tourists – yet.

Over at the other bank, we drove through pitch darkness across the sandy terrain for a few kilometers till we joined the road that came from Sunpura and headed for Tezu. An hour into the ride, the first signs of the headquarters of the Lohit district could be seen in the failing light.

It’s not hard to like Tezu. It looked like one of those quiet cantonment towns, leafy and wooded. With the sun all but down, the shutters also fell in the shops on the main street. We were to meet Uncle at the library and spend the evening amidst books and children. But the ride from Miao and the ghat crossing had taken longer than we had thought. So we decided to meet him at the Circuit House and catch up on the library visit early next morning.

The Circuit House itself was an expansive affair, located as it was on a large plot by the roadside. Almost colonial in its build, the rooms are spacious if basic. Anyway, there aren’t very many accommodation options in Tezu, otherwise. That kind of puts things in perspective and makes you want to be contented with what there is. By the way, it’s not easy to get a room in these, otherwise, government accommodations. And we had Uncle to thank for this.

He met us shortly after. It had taken us a long time to answer his invite. Every letter, mail, phone call, face to face chat would inevitably end with his asking us to come over and visit his beloved Arunachal. Over the years, the priority of this journey had got beaten up, and down, by many other commitments that come in the guise of practicality and everyday compulsion. But as so often happens in fiction – but rarely in real life – the good finally prevailed and our Arunachal trip materialized.

In the warm confines of our room, we sat talking, catching up on his work and filling him in with our eventful first three days of our trip. We were soon joined by his dear friends and well-wishers – Moyum an erstwhile student of Uncle and now working in the Land Management Department of the DC’s office in Tezu; Bapen another ex-student and herself well settled as an Urban Planning Officer (UPO) of Anjaw district; and, last but not the least, the smiling and unassuming Etalo, volunteer library activist and in charge of Bamboosa Library from its inception. We basked in the collateral regard and affection that these special friends of Uncle’s extended us and we opened up to them with the ease that you could only do, instantly, to Arunachalis.

We were in for yet another pleasant surprise. Just when we were feeling the effects of our lunch at Bordumsa waning, Uncle told us of what lay ahead for the evening. Hearing of our visit from Moyum, her friend and colleague, Basila didi had graciously offered to host us all for an authentic Mishmi dinner. It seemed that no time was being wasted in our being able to sample the flavour of our new destination – and we were grateful to Moyum and our host for the evening.

Basila didi lives in her Mishmi home in Tezu with her two children. Along with Moyum, she too works at the Land Management Department of the DC’s office in Tezu and is a well-wisher and a voluntary activist of the Bamboosa library. We walked into a house that was beautiful not just on account of the festivities of the Pooja season but also by virtue of Didi and her two adorable children.

For us, to say the very least, it was all utterly overwhelming. The day had begun with a farewell to Namdapha, a goodbye to the lovely Phupla Singpho family, a hearty ethnic lunch in Bordumsa, a memorable ghat crossing, a touching reunion with Uncle in his own special backyard…and now this. Being invited home by someone who we had never spoken to till then and being served authentic, delicious local cuisine in a chang-ghar…life doesn’t bless you with many of such days.

A word on the setting of the dinner and the food itself. The chang-ghar is, in these parts, an elaborate wooden structure built on stilts. Inside, the kitchen occupied one part of the room while in the middle was a hearth with a warm fire. We huddled around that and had what was, probably, one of the most memorable meals of our lives. A lal chai (black tea) and some small talk later, Basila didi’s main course arrived. Delectable dhekiya (fern) sabzi with a dal were suitable accompaniments for white sticky rice. But it was a tentative bite of the infamously hot Bhut Jhalokia pickle that set our mouths on fire, almost blowing the roofs of our palates sky high. We could barely murmur our profound appreciation and thanks for the meal and the exquisite gale (the local colourful skirt) that Didi presented. It was too much of an occasion not to be consigned to posterity.

The next day was when we would set off early morning for a long and exciting drive all the way to Walong. When that kind of a day is preceded by one as eventful as this, it’s a long night that separates the two. But we were tired…and tired we didn’t want to be tomorrow. Back at the Circuit House, it didn’t take long for the lights to be put out for the day.

A word also on our miss of the day. Dawns break early in that part of the country. We were earlier still. We wanted to drive in to Walong and see it while it was still light.

But before our long journey east, there was one important thing left to be done.

The Bamboosa Library. We were eager to put a form to what we had heard Uncle tell us about it all these years! Established on May 19, 2007, this was the first endeavour as part of the AWIC – VT Youth Library Network. Run by the Vivekananda Trust, headquartered in Mysore, there are now 13 of these mini libraries spread across the Lohit and Anjaw districts…most of them in the far flung villages higher up in the hills. There is more beyond the books stacked neatly in the shelves. There are frequent book exhibitions, reading sessions, workshops on improving reading skills, cultural and sports programmes, environmental awareness and much more.

The library itself is housed alongside a computer training school. Decked up with drawings and sketches and poems and photos and newspaper clippings, it is the true altar of the written word. Etalo, the resident head priest of this temple of books, joined us there soon after. There was already one keen young book lover and keeper of the keys, Purbi, already there. We spent a good part of an hour there lost among books, chatting up with the intent library volunteers and Uncle himself.

We wanted to stay back a little more but were happy that we could, at last, get here and see for ourselves the ground Uncle and his movement had covered. For someone who deeply believes in children and wants to get them to fall in love with books, the ultimate payoff would be for the young minds to recognise books as their soul-mates. That, for Uncle Moosa, is job done!

It was a long day ahead and, shortly, we were on the road again. As we passed the road that wound up to the serene Tafragam village, we remembered Uncle telling us of the even more serene VKV girls school up above. That would have to wait for a later visit to Tezu.

For now, we were headed for Walong. Names that we had till then only seen on the map or heard from Uncle were now on the road ahead. Hayuliang, Hawai, Walong, Kibithu, Kaho…the places would change, but there was one constant that would be a part of our 200 km drive up. And that was the Lohit – the river both beautiful and tempestuous, gushing down all the way from China and flowing into the Brahmaputra.

And then, in less than a week, we would be in Wakro! We would be with Uncle again and this time sharing his space with him – spending time with him at the Apne library, with his books, with his little patrons from Apna Vidya Bhavan and Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya, with the wonderful staff of these fine schools and, never the least, the two remarkable people who started and run these excellent institutions. But that will be quite another story and we will tell it once we reach Wakro.

For now, we were glad we were, finally, in Arunachal and with our dear Uncle Moosa!

Arun, Stilwell, Pangsau

This post is going to be different. I have decided to sit back and let someone else do the talking. My companion, my fellow traveller, and last but not the least, my better half is filling in for me this once. This post also has an emotional angle which might be better expressed by him.

So let me introduce to you my husband and my co-traveller, Rajesh.

A disclaimer. We have different writing styles. But we share the journey, the destination and the same spirit of travel and discovery. Here is his take on a nephew, a road and a pass – all of them special! So, over to him….

*** *** *** *** ***

We let the dust from the road shimmy around our feet and the silence wrap us from all around. In front of us stood the board we had traveled over 4000 km to see.

It read:

It was a sight we had seen without having been there. And it also wasn’t déjà vu. The scene had popped out at us in an album viewing session with someone who now has permanently found a place only in photos and memories.

Unlike the other posts in this blog, this one begins with an irresistible flashback of sorts; and I can’t help – figuratively speaking – bring to life (if only through words, which is what he loved most!) the person who I rank as one of my biggest personal losses – Arun Veembur, my nephew extraordinaire.

To sum up Arun in a few words is like trying to bring out the OED on an A4 sheet. But suffice to say, for now, that he was a brilliant student, an impossibly reckless but adorable human being, a fantastic writer, a traveler intrepid and a dreamer like no other. If you didn’t notice the tense in which I am forced to refer to him in, he is also no more.

Arun lost his life in a tragic mountain hiking accident in Dali, in Yunan Province, China. Out on a solo trek, despite being a trained mountaineer, he lost his way, his footing and his life on the rocky outcrop of the unforgivably treacherous Cangshan mountains.

Just how this brilliant young man, hailing from Kerala and born and raised in Bangalore, came to live and die in China has something to do with the Pangsau Pass. More than the pass itself, the object of Arun’s infatuation was a super-strip of vintage tar laid during the World War-II days by the Allied forces, christened the Ledo Road, later also immortalized as the Stilwell Road.

The Stilwell Road, named after the US General Joe ‘Vinegar’ Stilwell, was Arun’s muse and his dream project for the last five years of his 28 year old life. To travel it and write a book on it became his mission unto the very last.

Starting from Ledo, in Assam’s eastern most flanks, the road seems to have from thereon a mind of its own. Snaking through Jairampur, in Arunachal, and further down past Nampong, the last village on the Indian side, it lumbers on through the thick jungles bordering Burma. (Though renamed as Myanmar, in line with the spirit of the road and its legend, I have liberally used the country’s older name in many places in this post. There is something mystical, almost magical that seems to ring with Burma and things Burmese!)

Beyond the border, it surfaces up at Pangsau village – the first on the other side – and continues onwards in its undulating journey up and down the mountains and entering China to further soldier on till Kunming. That is a journey of no less than 1736 km. Meant to be the lifeline to transport men and arms to help the Allied forces battle the Japs, the road was built at great human and financial cost over some of the most impossible terrains in under two years. The unsung heroes who helped build it were a staggering 40,000 plus – Britishers, Americans, Indians, Burmese and those from nearly every nation that were part of or stood with the Allied forces contributed unremittingly to the cause.

It is famously retold that, during an air sortee over the mountains one monsoon during the war, Lord Mountbatten enquired the name of the river he thought he saw down below in the Hukawng Valley. No, he was told, that was no river. That was, in fact, the Ledo Road. And just how tough the Pangsau leg of the road is, reflects in the name they gave the place – Hell’s Pass.

It must have been stuff like that which must have inspired Arun. For someone like him, it was also not difficult to inspire others. Let me hasten to clarify that ours was not to try and attempt a crossing of the Stilwell Road. At best, our visit to Pangsau Pass and a drive down the iconic road was a pilgrimage – an undying tribute to someone for whom the road meant a lot, his life.

We flagged ourselves off on the day after Dussehra and our starting point, Tinsukia, and the whole of Assam was at her festive cheeriest. Despite the permanent smile he wore, we suspect that Das – who is fondly called Dasda by anyone who he has driven around the North East – was not entirely mirroring that feeling…what with having to be on duty after a night out at a pandal. But to his credit, it soon became clear as to why he is so regarded so highly – both as a driver and a travel companion.

Our stopover at Digboi was followed by a drive through the towns of Ledo and Lekhapani till we got to the point that formally announced the beginning of the Stilwell Road.

This was where Arun had got to about 5 years ago and told us about the goosebumps he had felt. At around noon on the 6th of October, 2011, we were to feel the same. We were 12 km away from Jagun and 24 kms from Jairampur, the last town in Assam and the first in Arunachal, respectively.

We were handed over our Inner Line Permits at the Jairampur checkpost by none other Mr. Arif Siddiqui, an accomplished photographer and the man behind www.amazingarunachal.com, an excellent resource on Arunachal tourism. Mr. Phupla Singpho, our friend at Miao and who runs his own NGO promoting tourism in Namdapha, had helped us with these permits and, of course, our Namdapha visit later in the trip. Our documents found to be in order, we felt another ray of current pass through us as we stepped foot in Arunachal for the first time!

Lunch was at a smallish restaurant – more dhaba – and further on we passed the Assam Rifles cantonment.

Our next stop was at the Vivekananda Kendra school where we had a wonderful meeting with the charming principal, Dubeyji and the administrator, Ramachandranji.

One of the earliest in a pioneering chain of educational institutions in Arunachal, we saw up close the serene premises of VKV, Jairampur and walked around the classrooms, the boarding dormitories and met up with many of the students there.

Continuing on the Stilwell Road, we were now headed for the World War II cemetery. About 7 kms further down from Jairampur, we were driving slowly lest we should miss it in the thick overgrowth.

But we were pleasantly surprised to see that it had now been bestowed some respect and had a prominent entry gate, making it hard to miss on your left.

We spent some time among unknown gravestones and randomly meandering paths. It was somewhat eerie with the silence from the remoteness of the place and the fact that we were the only two living amidst the many departed and underground. After spending an hour or so with the martyrs, spotting a few butterflies and clicking a few photos, we left for Nampong, the easternmost Indian habitation on the Stilwell Road.

It was getting on dark and the road was, by then, taking a turn for the worse. Eventually, after being stopped briefly at an army checkpost, we drove into Nampong even as the sun was all but down. We were booked into the Nampong IB which was a little way above the market place and just before the checkpost that screens movement onwards to Pangsau Pass and Pangsau village.

The IB itself was a tidy arrangement, with an old wing and a new. There was ample parking space and the whole premises overlooked Nampong town, the surrounding mountain range and a brilliant sunset. We walked into the strains of music wafting about and were told that there was a music band that had drove in all the way from Guwahati to play in the Pooja pandal that was set up in town. And, post dinner, we settled down to some seriously elevated balcony seats, in the lawns of the IB, and watched and heard the band play to an appreciative crowd down below.

We were up early morning and found Dasda giving his car a thorough wash. Packed, we were ready to head out to Pangsau Pass and be back before noon. Our chat with the IB staff, the previous night, had prepared us for some rather uninspiring news. We would not be able to cross over at the border and would have to miss the Lake of No Return and Pangsau village. Visitors from only either one of the nationalities could cross the border on a given day. It was a Friday and Fridays were Burma Day – which meant only Burmese villagers could cross over. Indians could go over only on the 10th, 20th and 30th of each month. If it weren’t a Friday, we could still have worked out some arrangement. Guess we would have to return to Nampong during one of the Pangsau Pass winter festivals – usually held in December – some other year.

After a brief stop at the checkpost outside the IB, we were flagged off. While we were waiting, we saw the first batch of Burmese villagers, with their baskets, walking up. Some were a little wary while others looked away but what caught our attention was they were nearly all women and children, hardly any of the menfolk.

We drove on through absolute wilderness. Wooded slopes dotted the hills around and the dust rose menacingly from the under construction road. In places, Joe’s road was as unmanageable as the Japs had been during those days. Dasda just took it all in his stride even as he kept up an amiable commentary on the region and its people.

All throughout, we noticed more but small batches of villagers walking in, chatting and giggling among themselves, unaware of clicking cameras from passing vehicles! Talking of passing vehicles, there were actually none other than ours. Except for a run down, open backed van that plied up and down and made a good fast buck out of the hapless villagers, saddled with their purchases on the way back. The going rate, Dasda added, was Rs. 100 per person for a ride.

We noticed something else. As a kind of travel insurance, the women had smeared their faces with some paste; apparently, this was to de-beautify themselves…strangely, leaving home is not always about looking good.

At one place, the road split into two. One of them, the more decrepit, was the old Stilwell Road while another, newer branch had carved its own modern day identity.

We must have travelled about 12 km when we spotted a motley congregation ahead. We were at the border checkpost and the Indian Army was screening the Pangsau villagers. Sure enough, there were the green uniformed Indian guards, some of whom were busy checking documents. The large majority of the visitors just squatted and hung around all over, waiting for their one day permit that meant a week long stock of goods ranging from salt to clothes, bicycles to batteries and, yes, booze!

Over to a corner by the roadside, there were a dozen or so rundown mobikes without character or number plates, dumped to one side. These, we learnt, belonged to some of the more ‘affluent’ villagers who had, at least, saved on trudging the distance from their village to the border.

There were about fifity odd of the villagers and about half a dozen soldiers eyeing us. Dasda did the honors by introducing us to a senior Army man who promptly arranged for one of his men to escort us till the official border. Dasda chose to stay back and we set off with our new friend who seemed to carry his full rifle and a half smile with equal ease.

With a shyness that didn’t quite gel in with his profile, he opened up with a little conversational support from me. Our escort, deferential but smart, was Baithye from Manipur and was currently posted to this outpost. There were not many Indian tourists, he told us, who made this journey. Of course, there were the villagers from Nampong and the crowds that thronged during the Pangsau Pass winter festival. But, I realized, it was only the oddball Stilwell enthusiast who dropped in and that wasn’t a number to worry the Indian Army much!

We had turned a corner and were out of sight with the horde we had left behind. And, presently, we spotted the board I began this post with. We were at Pangsau Pass!

It was impossible not to freeze the moment and save it for posterity. We gladly let ourselves be shot by a soldier. Of course, he had tucked his rifle aside and gingerly felt his fingers around my D90 and fired the first round. I requested him to share the frame with me while Malini played soldier.

We were now at the spot which, the board above us said, was the Indo-Burmese border. The checkpost of the Myanmar army was still a few hundred metres away, beyond another bend in the road. In the absence of a proper permit, reaching the Burmese checkpost was a no-no. We did, however, walk a few metres further on before turning back.

Burma had just been a few strides away. Two kilometers across the checkpost lay the village of Pangsau and not too far away the mysterious, almost mythical, Lake of No Return. This waterbody gets its somewhat intriguing name from a piece of world war folklore that likens it to the Bermuda Triangle. It is said that, during WWII, an unverified number of Allied aircraft that flew over the lake had either crashed into it or simply disappeared. Adding to the mystery are also reports of soldiers, including those working on the Stilwell Road, having stepped into the lake and losing their lives. In fact, the Lake of No Return figured prominently in the joint scheme mooted by the Indian and Myanmar governments to promote tourism in the region. For now it had, tragically for us, become the Lake of No Entry!

Back at the Indian checkpost, we bid our new Manipuri friend goodbye and drove back. We passed more villagers – both on foot and cramped into the open vans – and wondered if there was any wonder that they ever felt for the road that had drawn us like a magnet all the way.

As we drove back into the IB, we noticed a trickle of villagers leave the road, skirt the edge of the IB premises and take a shortcut down to the market below, saving them a couple of kilometers had they taken the road. For us, this was a once in a lifetime visit down Arun’s road. For them, the weekly hike was all about getting food, and other essentials, on the table back home.

Breakfast over, we were driving out of Nampong, headed for Miao for the Namdapha leg of our trip. As we passed the marketplace, Dasda slowed down to show us groups of Burmese villagers busily shopping around. They were huddling around hawkers, queuing up for liquor, flitting from one shop to the other…no one was a wanton tourist. There seemed a definite purpose to their long, painful international hike they made early morning.

Driving down the Stilwell Road for one last time (at least in this visit), we remembered Arun. Twice he had reached Nampong and turned back…only to come back and go the whole hog down the road that meant everything to him. He too had stayed at the Nampong IB, clicked himself to posterity at the sign board at Pangsau, went further down past the village and onwards to Myitkyina in Burma to reach Kunming in China.

But his journey was still only half done. His travels on the road was just half his mission. The other half was the book he so wanted to write. All we have today, as Arun’s dream, are some photographs and a few opening chapters that he left behind. Going by that alone, it was clear that it would have had all the purpose that the Stilwell Road was meant to have. But, as with the road itself, all that we are left with is the beguiling aura, the undying charisma that Arun’s book holds in eternal promise.

In Namdapha: Chasing the Butterflies

The alarm on my mobile phone was set at 4.30. But I was woken up before that. By a steam engine, of all things.

A steam engine in the middle of a jungle! The nearest railway station was about 90 km away, in Margherita, Assam.

I ran outside to see if the Hogwarts Express from Platform 9¾ had changed its course into this magical land. The sound was coming from somewhere up, from the branches of a tree. Seeing me dash outside in my night clothes, Gogoi da came out from the kitchen and joined me outside on the lawn. He pointed up and said “Hornbill”. At that very same moment two hornbills flew away flapping their wings vigorously.

I later learnt that the wing beats of a hornbill are so heavy that the sound produced by the birds in flight can be heard from a distance. When flapped, their wings create loud whooshing sounds that resemble the puffing of a steam locomotive starting up. Even their deep echoing calls can be heard from miles away.

Gogoi da rushed back to the kitchen to get us our tea and we walked towards the river to enjoy the dawn.

My alarm just went off. It was only 4.30 in the morning.

The sun was rising somewhere behind the high mountains. But the golden rays were already making an impact on the sky and the river in front of us. It is hard to explain the way we were feeling – completely at peace, far away from the noises of the city, the honking, the shouting and yelling.

While sipping our tea we heard the loud whooping of hoolock gibbons. We followed the evocative call which led us into the woods behind the rest house. It was very difficult to judge from where the noises were coming, but the sounds got louder. It was as if they were somewhere right above our heads. But it was so hard to spot the gibbons through the thick foliage. It seemed as if more than one group were there and some sort of a hooting competition was going on. We had strained our necks for quite a long time so we decided to get back to the rest house.

It was barely six in the morning and so much had already happened. Such is the magic of Namdapha.

We had an early breakfast. Mr Pungjung had told us the previous day that if we had to spot wildlife we were to start early .

So we set off from the rest house armed with our cameras, binoculars, a book on butterflies and a lot of enthusiasm along with our guide, Mr Pungjung.

Mr Pungjung had 33 years of service, out of which 18 years he had spent at Deban. And he didn’t even look 33. There was a sprint in his walk, a twinkle in his eyes and he was always at least 50 m ahead of us, patiently waiting for us if there was something interesting to be sighted.

And interesting it was.

We took a shortcut from the guest house, cutting the hills and reached the Miao-Vijoynagar road and started walking towards Vijoynagar. Deban is called the 17th mile. We had planned, or rather Mr Pungjung had planned, that we would walk till the 22nd mile to get some views of the mighty Dapha Bum.

The jungle was replete with bird calls.

We got to understand the spectacular bird life present here. In the small muddy streams we saw forktails hopping around, while other birds included the flamboyant scarlet minivets, babblers, tree pies, barbets, patridges, kingfishers ……..

The sun was climbing up, slowly. Till then we were passing through thick forest and the mud path was mostly covered with shade. Suddenly we came out to an open space, a small meadow, and realized how hot it was. But we did not feel the heat, as there was something that lay before us that cooled everything around us.

Butterflies.

Namdapha is a veritable butterfly paradise. Perhaps one of the prettiest insects on the planet, butterflies embody the spirit of beauty and transformation in nature.

And what we found in front of us looked like a colour palette with multitonal hues and designs. Mr Pungjung started to identify the butterflies and I was busy noting them all down. Somewhere in the middle I gave up, the zoological names were distracting me from enjoying those fragile and pretty creatures.

Great Orange Tip’s, Common Five Ring’s, Chocalate Pansy, Evening Brown, Plum Judy, Common Mormon, Common Sailor and Common Crows kept flitting by. The dragon flies and moths were not far behind.

I was distracted again, this time not by the Zoological names but by something more profound. It was the Gibbons again, those loud, coordinated, stereotyped duet song bouts had started again. Mr Pungjung said they were somewhere nearby.

We walked further up the jungle trail. The sounds got louder. And we spotted them. And ‘they’ consisted of a small happy family of a mother, father and child. The mother was swinging from a branch with her baby clinging on to her, her husband watching her carefully from a neighbouring branch.

They suddenly disappeared into the thick forest cover and we moved on, their sounds still haunting us.

On the way we found remnants of small fires that had been rustled up along the roadside. They had been made by people belonging to the Lisu tribe. About 157 km from Deban lies a small village called Vijoynagar. A succession of earthquakes, landslides and rains have made the settlement inaccessible and the only way to reach this village is on foot. Vijoynagar is inhabited by the Lisu tribe, who hunt forest animals. This has caused a lot of friction between the Lisus and the forest department. Poaching is common in these forests. There has been instances where Lisus have tried to exchange the endangered Red Panda for a packet of salt!

There are hardly any shops in Vijoynagar, so they have to trudge through the forests, cross the river, defend themselves from wild animals and sometimes walk in the rain to Miao to do all their shopping.

We met a few Lisus on our way, they carry bamboo baskets on their backs, loaded with provisions walking slowly through the jungle. It takes them around 10 to 11 days to reach their village depending on the weather.

It was already 12 pm and we started walking back. We were too engrossed with the forest sights, we totally forgot about the river flowing by, down in the valley.

The sky was overcast and it looked as if it was going to rain. By 2.30 we were back at the guest house – and then it started to rain.

Famished, we decided to have lunch first.

Back at the cottage, we realised we had brought in some of the jungle’s fauna along. My husband took his socks off to reveal a particularly obstinate leech clinging on to his ankle – our first encounter with a bloodsucker. Fortunately, I had remembered my lessons…..a drop of saline and the little fellow dropped off, leaving behind a wet, red smear; our predator squiggling away for its next unsuspecting prey.

We sat by the river in the evening. It had been an eventful day. The day’s excitement and tiredness began to take its toll. Before long we were asleep, lulled by the river flowing by and the occasional hoot of an owl.

The next day we were up before 5 am. This had become our daily routine – sleeping early, getting up even earlier – ever since we started our trip.

By 7.30 we were on the road, again. Today we were to walk towards Miao, as long as we could.

Across the river we spotted a small village with a lot of stilted houses. This village belonged to the Chakmas. The Chakmas are refugees from Bangladesh and are relatively recent immigrants, having been settled by the Indian government in the western edge of Namdapha.

Mr Pungjung kept spotting animals and birds. By the time we came running with our cameras they conveniently disappeared. I did manage to capture a Malayan Giant Squirrel and a few hornbills flying by.

The patient trekker has a chance to see what he wants. The entire area is filled with songs of different species of birds – from cuckoos to tree pies, redstarts to whistling thrushes, finches to sunbirds – the list is, happily, never-ending. The pretty flowers found in the shruberries and undergrowth added to the beauty of the forest. The oaks, the bamboo thickets, ferns and wild orchids all over.

A lot of road repair work was going on, a bridge was being revamped, ahead of the trekking season

There were surprises everywhere. A blue whistling thrush crossing the road, hornbills gliding over the tree canopy and a group of cape langurs enjoying their afternoon siesta.

But it was time to go back. As we walked back we felt as if we were in a trance…taking the whole rainforest in.

But then I was reminded of a quote by Charles Darwin – “Delight is a weak term to express the feelings of a naturalist who, for the first time, has wandered by himself in a rainforest”. How true. Truer still, in this paradise called Namdapha.

But there was more to come. More to see. And more to know about.

The battle fields of Namti, near Walong.

Kaho and Kibithu – the eastern most villages of India.

Wakro and Tezu – our homes away from home.

Watch this space for more..

In Namdapha

It was 5 pm and the sun was already on the wrong side of the horizon. The flickering solar lights at the forest guest house we were staying at looked feeble from where we were standing. We were atop a small mound of sand overlooking the Noa-dihing River. The only sounds we could here were the occasional flaps from the birds, flying back home, and of the river making its way through its pebble-strewn bed.

We were at Namdapha National Park.

Namdapha National Park is the largest wild life sanctuary in India, with a total area of 1985 sq km, and is located in the Changlang district of Arunachal Pradesh near the Myanmar border. This park is recognized as one of the richest areas in biodiversity and has the credit of being the northernmost evergreen rainforest.

The previous evening we had reached Miao, a village located on the fringes of Namdapha. Miao is a small settlement with some modern government quarters, a few traditional Singpho houses, a Buddhist monastery, a mini zoo and a museum, an inspection bungalow, an eco-tourist hut and a cute little market.

Our friend and host, Mr Phupla Singpho, had already arranged for our stay at the eco-tourist hut for the night. He stays in his very modern concrete house with his family right opposite to his more traditional wooden family home. He has been instrumental in bringing global importance and interest to the Namdapha National Park.

The Singpho tribe of Arunachal Pradesh inhabit the district of Changlang and are mainly Theravada Buddhists. They are traditional tea planters. The Singpho produce their tea by plucking the tender leaves and drying them in the sun and exposing them to the night dew for three days and nights. The leaves are then placed in a hollow bamboo and exposed to smoke over a fire. This way, their tea can be kept for years without losing its flavour. Mr. Singpho presented us with this ingeniously produced tea. I felt a bit awkward presenting him in return a plastic packet of Coorg coffee.

After checking into our room at around 2 pm, we had a couple of hours before sun down. Yes, the sun sets in these regions very early and before 5 pm the street lights are on. There is a serious demand to have a separate time zone for the northeastern states with suggestions for advancing the clock by at least 90 minutes. This is because the day breaks early in the northeast with the sun normally rising way ahead of other Indian cities. When we were in Miao in October, the sunrise was recorded at 5.05 am and the sunset at 4.55 pm, where as the same in Bangalore, where we stay, was recorded at 6.10 am and 6.07 pm, respectively.

The British were smarter. They had set the local time one hour ahead of IST for tea gardens, coal mines and the oil industry in these parts. Some of the tea gardens still follow the bagaan (garden) time!

Before sun down we decided to visit the Singpho monastery nearby. We were welcomed by a group of dogs who were loitering around the monastery.

The monastery itself is an imposing structure painted with vibrant colours of yellow and maroon. Narendar Bhikku, the head monk, was kind enough to spend some time with us, even presenting us with a book on Buddhism.

He had been staying at this monastery for more than 40 years. The altar had numerous idols of Buddha and there was a stupa and a Bodhi tree outside.

The museum and the zoo were already closed, so we walked back to the eco-tourist hut, had dinner and slept early.

About 25 km and 2 hours from Miao lies Namdapha National Park, a wildlife enthusiast and biologists’ dream come true. The next day, we stocked up on our dry provisions from the market and started our journey around 8 am in a Tata Sumo. The road on the way is so bad that only the bigger vehicles dare to venture into the forest. We were first stopped at a check post manned by the 18 Assam Rifles. The army is overpowering with its presence in Arunachal Pradesh and you can be stopped at any check post. Visitors entering the state are checked for their Inner Line Permits and Tourist Permits that must be obtained before entering the Namdapha National Park.

Our host had arranged for our stay at Deban, the forest headquarters within the park and the only accommodation option at Namdapha. The drive takes you through a jungle path that may take about an hour-and-a-half, depending on the state of repair of the roads or the intermittent landslides that occur in these regions. We were lucky not to face any landslides. We crossed the bridge over the Noa-dihing River, some traditional houses on stilts on the edges of paddy fields and reached M’Pen stream, a perennial stream that normally overflows during the rains.

Our driver said that visitors to Namdapha during monsoons often have to wait for up to two days for the stream to subside before it can be crossed by their vehicles. Sometimes one might even have to start walking from the M’Pen stream which forms the boundary of the park. As soon as we crossed the stream we reached the park entry gate and our credentials were checked by the Forest Department staff posted there.

The rest of the journey took us through a thick jungle. It seemed as if the sun had already gone down, and it was not even 9 am. On one side of the jungle path there were tall trees rising up to 100 m above us with a thick undergrowth of ferns, cane and bamboo. On the other side beyond a gorge, the Noa-dihing river was following us.

We passed a small temple, turned a curve and reached a cross road. There were two roads, one going downhill to the forest guest house at Deban and the other going uphill all the way to Vijoynagar, 157 km away, right on the India-Burma border.

We followed the road downhill and reached our home for the next three days and nights. The Deban Rest House is located within the Namdhapa National Park and is managed by the Forest Department of Arunachal Pradesh. The rest house stands on a thickly wooded hill slope overlooking the Noa-dihing River. The mysterious forest seems to engulf you and certainly there can be no better option for the adventurous.

We were booked into a double room on the ground floor in this conical shaped rest house. The more luxurious top floor rooms were meant for government officials and VIPs. Because we were neither, we settled for what we got which was the next best. Tourist huts, dormitories and traditional huts are located away from the main structure towards the river. Right next to the main rest house is a mess room where meals are prepared by Gogoi da and his efficient team.

There is no electricity in the park. The rest house is electrified by solar powered batteries. There is no public telephone service in Deban and our mobile phones were happily hibernating inside our backpacks. Once a day, and if any emergency arises, a wireless is used to communicate with the outer world.

Namdapha Park is unique in many ways. Declared a Project Tiger reserve way back in 1983, this is the only park in the world which has all the four big cats; the Tiger, the Leopard, the Snow Leopard and the Clouded Leopard. The reason being the region’s varying altitude, it ranges from 200 m to more than 4500 m. The Dapha bum, the tallest peak in Arunachal, overlooks the park and is snow covered during winters. Namdapha is also home to India’s only ape, the Hoolock gibbon. And the most unique factor – Namdapha is one of the few national parks in India which you can explore only on foot.

The first thing to keep in mind when you set out to explore this area is that you must do it in the right season. In the monsoons the jungles are inaccessible, the river uncrossable and the blood-sucking leeches are out on the grounds and tree tops looking for preys. Yes, on the tree tops. There are about 5 species of leeches and some can even sense the human blood from about 10 feet away. There are leeches that hide in the ferns and branches and jump onto you from above!!

We visited Namdapha in the right season. The river was flowing low, it was not the rainy or snowy season, but the forest staff were a bit behind schedule in clearing the jungle. It is an annual ritual of the forest staff to clear the jungle by marking well-defined trails for the convenience of the trekkers and wild life enthusiasts. There are camping sites inside the jungle at various places.

Entering the jungle was out of the question for us. But the rest house surroundings is a mini zoo in itself. The whole place was swarming with butterflies, and it was not even season. The constant sound of the crickets seemed like an alarm clock that somebody forgot to turn off. And there was even a small snake lurking among the bushes right in front of our room even as we were checking in!!

By the time we had checked in and freshened up, it was time for lunch. After lunch we decided to explore the park by ourselves. We walked up the road on which we had come down a few hours earlier. The sounds of the jungle were mesmerizing.

A lot of birds were singing, hooting and clucking away merrily in the foliage. The constant sound of the river flowing by, adding up to the melody. As is normally the case, it is so hard to spot birds and even harder to photograph them. The luck with butterflies were better.

The sun was going down slowly and we decided to walk to the river side. A small concrete platform was built overlooking the river. But we walked down further to the sand mound to get a better view. The mound makes a perfect natural watch tower to check the river below, giving you good views of the huge mountains across the river.

Right next to the watch tower is a huge tree belonging to the Ficus species that towers over the guest house with its height and appearance. The lower portion of the trunk is split and it looks as if the tree has two legs, ready to walk away.

The sun was down in a few minutes and there was nothing to do other than enjoy the night sounds coming from the jungle – the occasional hoot from an owl, the crickets with their raucous calls and the cry of the barking deer somewhere nearby only enhanced the surreal nature of the surroundings. The sight of the huge yellow moon, whose glow surrounded the valley was overwhelming. We decided to turn in early as we had a long day ahead of us.

For the next two days we had planned to trek along the jungle road and had already spoken with the in house wild life enthusiast and expert Mr Pung Jung.

Tomorrow was going to be busy. There were butterflies to be captured (on lens), birds to be identified, and leeches to be dodged. And if lucky, we could even spot a Hoolock Gibbon, a Hornbill, or one of the four big cats……

I love to be optimistic.

Bridges of Arunachal Pradesh

In the 1992 best seller, ‘Bridges of Madison County’, when National Geographic photographer Robert Kincaid drives his pickup truck through the hot and dusty dirt tracks of Iowa and turns into Francesca Johnson’s farm driveway looking for directions to the Roseman covered bridge, little did I know about the beauty and romance of the bridges of Madison county that would haunt me forever.

I found the same beauty and romance in the bridges of Arunachal Pradesh too.

Arunachal Pradesh: the land of the dawn-lit mountains, the land of the Hoolock Gibbons, the land of the Mishmi’s, Adi’s, Tani’s, Nishi’s and many other indigenous tribes, and the land of the fiesty Lohit river.

Someone had said that ‘Bridges are perhaps the most invisible form of public architecture’. But not in Arunachal Pradesh.

Bridging rivers, gorges, and valleys bridges have always played an important role in the history of human settlement by not only providing crossings over water, dangerous roads and cliffs, but also becoming ‘frames for looking at the world around us’.

The beauty of each bridge that we crossed in Arunachal Pradesh was inspiring. Each one had its own unique character. Whether we were driving or walking over them or passing under them, we were enamored by the beauty of the surroundings. Some of bridges were monuments on their own.

Some of the hanging bridges we crossed were made of bamboo and wooden planks, apart from the metal cables that ran along the side and connected them to the ends. The floor creaked and squeaked, the entire bridge sometimes swinging under our clumsy steps. Below, through the gaps of missing wood pieces, we could see the mighty turquoise Lohit river gushing and rushing loudly, leaving us breathless.

And then you see school children running across barefoot, mothers with small babies on their back, villagers carrying loads of whatsnot in their bamboo baskets, looking at us suspiciously. Well, practice does make one perfect. But what about fear of heights. Must be non-existent in these places.

A lot of the modern bridges in Arunachal are built by the Indian army and Border roads organisation.

Metal and concrete structures that are built to withstand the rains, landslides and the heavy army trucks. Though they do not have the beauty of the hanging bridges, they do serve their purpose.

Have you heard about bridges that are not built? Bridges that are grown.

Maybe, some other time….