Mohammad Anwar looked older than the photograph on his guide ID card, pinned to his front pocket, that he flaunted proudly. The once-pure-white-now-off-white soiled Kurta and Pyjama he was wearing, showcasing the muck and grime of the alleyways of Bijapur, and his unkempt beard, only added to the degree of scruffiness. He had bags under his eyes and deep lines around the corners of his mouth. Being a Tonga driver must be tough.

The moment we stepped out of the railway station in Bijapur in our touristy attire (backpack, camera, Bisleri bottle et al.), we were swarmed by a group of heckling auto drivers vying hard to get our attention. From what we had researched and understood, we knew that the nearest ‘sightseeing option’ was a kilometer and a half away from the railway station.

Bijapur Railway Station

In order to wave off the crowd, we started walking as if we owned the city, following a yellow board which clearly said that the Gol Gumbaaz was 1.5 km away, when we were stopped in our tracks by a soft but earnest voice. “Sirjee, tonga mein jaana hai? (Sir, would you like to go in a horse carriage?)”.

The Tonga!

The magical sound of the horse’s hoof beats … clip-clop, clip-clop, clip-clop. Doesn’t it bring back a lot of memories? Right from my school days, when I used to feel jealous of my class mates being ferried by the ‘vandichettan’ to the later days of watching Rangoli on DD 1 while the Biswajeeths and the Dilip Kumars serenaded the Sadhanas and the Vyjayanthimalas, there was something I felt very romantic about a tonga ride.

Tonga

The painted carriages, the seats in the brightest of colours, the rainbow feathers in the horse’s bridle and the royalty attached to a horse-driven carriage.

Tongas have been an integral part of the Indian roads, right from the time of the mighty emperors, princes and princesses who must have trotted about proudly in their elaborately decorated carriages. The advent of automobiles failed to dampen the business of the horse-driven carriages, which continues to enjoy mass popularity.

Of late, places like Delhi, Lucknow and Agra have been trying to bring in these colourful horse carts that would trot off to historical sites, with guides clad in white kurta-pyjamas and Lucknavi jooties, bringing back the charm of the old days and sprucing up tourism in those cities.

Our guide-cum-driver, horse and carriage seemed miles away from that mere thought.

The paint on the carriage was peeling off in places, the sponge was coming out of the seat cushion, the wooden wheel spokes were chipped, a huge stone was kept on the foot rest to keep the cart in balance, the horse was a bag of bones held up with skin and the driver, Mohammad Anwar, looked far from being the smart tonga driver.

We looked at each other, unable to decide whether to take the ride or just walk off, avoiding him. But it was difficult to dismiss him as we had ignored the cackling auto-drivers, and we found ourselves climbing onto his tonga ready for our vintage ride through Bijapur.

Bijapur – The capital of the Adil Shah Kings from the 15th to the 17th century. Ruins of forts, palaces, mosques and mausoleums lie scattered around the city, celebrating the renowned symmetry of the Islamic architecture.

Riding out of the railway station, we followed the Station Road, now christened as the Mahatma Gandhi Road. The tonga took a sudden left turn, and right in front of us spread the magnificent Gol Gumbaaz. The tonga did not stop and sensing the disappointment in our eyes, Mohammad Anwar said that the Gol Gombaaz would be our last stop in this ride.

Various hues of Bijapur

The tonga took us deep into this maze, like a labyrinth, of alleyways that gave us a feeling it had not been changed much over the centuries. The houses painted in different hues of green, remnants of the old city crumbling to pieces and encroached upon in places, streets with rickshaws, cows (and cows and cows), pigs, goats, women fully covered in black purdah, small children rushing to their Madrasas – girls covering their heads with their scarves and boys wearing the customary skull caps. Bijapur was like a period classic playing out splendidly before our eyes.

Our first stop was the Jama Masjid.

The Jama Masjid, built in 1686 during the rule of Adil Shah I and to commemorate the Talikota victory, is one of the first and largest mosque’s in Bijapur.

From outside it looked unimpressive, a grey stoned structure with small arches built into the walls. Vendors of different kinds were trying to sell their wares, tourist maps, fruits and little knick knacks. Somewhere inside the Masjid there must be a Madrassa, as we found little girls and boys running around, books in their hands. Groups of elderly men were sitting on the steps and on the smaller walls, smoking, chatting and mostly doing nothing.

The wait – outside Jama Masjid, Bijapur

Our first chore was to buy a pamphlet showing all the tourist spots in Bijapur from an old lady sitting on the steps of the mosque. We climbed a flight of stone steps and passed into a huge rectangular hall. Once we entered inside the mosque, we realised how grand this monument was. The hall continued on three sides, enclosing a small tank in the middle, and was lined with high arches that divided the hall into 45 compartments, each with beautiful carvings. Above the hall resting on the beams was a dome, shaped like an onion. The masjid is said to accommodate about 2250 devotees; the floor is painted with 2,250 squares for each worshipper.

Inside the Jama Masjid in Bijapur

We took off our foot wear and walked around taking in the beauty and largeness of the mosque. There was barely anyone in the prayer hall, only a couple of praying men absorbed in themselves. In front of the main hall, the wall is adorned with golden paintings and inscriptions, the lower portion faded by the continuous touching of devotees. Now a bamboo barricade and a stern Maulavi stands, or rather sits, between the wall and you. The mosque holds an exquisite copy of the Quran written in gold letters.

Other than the pigeons flapping and the little girls giggling in their class rooms, there were no other sounds. How majestic this structure would have looked, back in the 16th century?!

Seeing our cameras, a couple of girls surrounded us asking us to take their photographs.

Inside the Jama Masjid in Bijapur

From the Jama Masjid the tonga took us further down the busy inner roads. The horse stopped suddenly by the road and our guide pointed to a beautiful building and said ‘Mehtar Mahal’. We would not have noticed it if he had not pointed it out. ‘It’s the gate to the Mehtar Mosque’, he said ‘and closed for renovation’ he added.

Mehtar Mahal looked more like an amalgamation of a haveli, from Rajasthan, and a Hoysala temple from Karnataka; probably only the two minarets on top giving away its Moghul origins. This three storey building had a lot of carvings in Hindu architectural style – we spotted lotuses sculpted on to the walls. The brackets resembled the mythical creatures we had seen in the temples at Belur and Halebid.

Mehtar Mahal

We resumed our journey through the small road till we reached a busy circle. From there the roads got wider and we were passing through some of the main market area.

We stopped in front of a domed structure. A second glance revealed another dome peeping out from the side. The Jod Gumbaaz it was – the twin domes of Abdul Razaq Dargah. Built around the late 1600s, the domes hold the tombs of Khan Muhammad and Abdul Razzaq Qadiri. According to a metal hoarding belonging to the Karnataka Tourism, the two men – one the general and the other the spiritual advisor of the Adil Shahi family – were considered traitors as they helped the Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb, defeat the Adil Shahi ruler, Sikandar.

Jod Gumbaaz

As we entered the gates of the Jod Gumbaaz, we realised that, other than the larger twin domes, there were other smaller ones around the complex. There were neat lawns with huge shady trees, a respite to visitors on hot sunny days. Some of the trees had small shrines at the base.

We walked towards one of the domed structures. At the ground level of the tomb was a dargah. At the entrance, we found an inscription from the holy Quran painted in green. There were people, mostly ladies and children, sitting in front of the entrance of the dargah. The Maulavi was reciting some prayers and offering them holy water.

Without disturbing the religious fervour, we walked around the dargah. This must be an important religious centre for we found several people staying in the complex, setting up small makeshift sleeping places, clothes hanging around to be dried and food being cooked on brick fire places.

Domes, tombs and shrines at Jod Gumbaaz

The tombs painted a beautiful picture against the skyline.

It was time for our next stop. The tonga took us further to Taj Bawdi.

When the Bahamani emperor, Ali Adil Shah, brought down the Vijayanagar empire in the mid 16th century, other than building palaces and mosques, he also undertook the task of improving the public water supply system in the city of Bijapur. His son, Ibrahim Adil Shah, built Taj Bawdi in 1620 for his first queen, Taj Sultana.

In its heydays, this monument must have been a bustling place with weary travellers. Now a sole security guard sits with a stick that does the job of shooing away stray dogs or to poke back the cricket ball that’s hit in his direction by kids playing in the lawns outside.

Taj Bawdi

You are welcomed by a huge arch which is flanked by two towers on both sides. These octagonal towers used to be rest rooms for the travellers. We passed beneath the arch and climbed down a flight of stone steps to reach the tank. A stone wall skirts the three sides of the tank, covered by arch windows, that had rooms meant for the use of travellers. An iron gate has been built to prevent people from entering the water.

And why would one enter the water? The tank has turned into a dumping pit. The garbage of Bijapur is finding its way into Taj Bawdi, once the sole water supply of the city. The water was green and stinking. We learnt from Mohammad Anwar that the Karnataka Government, after declaring Taj Bawdi as a protected monument, had spent around 8 lakh rupees in 2005 to renovate the tank, remove the waste that was dumped here and refill it with clean water. But without realising the national importance of this monument, people started to use the tank to wash the clothes and to dump garbage, again.

Dirty waters at Taj Bawdi

Now the iron gate and security guard ensures that we do not see boys frolicking in the water or their mothers washing dirty clothes. But it is sad to see that, still, the cities’ garbage mysteriously finds its way into the tank. Plastic bags lay strewn on the steps of the tank and immersed in the water.

We climbed onto our royal carriage for our next destination. By this time we had already learnt the art of climbing with ease.

Our next stop was the Ibrahim Rouza, arguably the second most striking monument in all of Bijapur.

Ibrahim Rouza

Ibrahim Rouza was built by Ibrahim Adil Shah II as a mausoleum for his wife, Taj Sultana. Ironically, the emperor died first and was buried here. This huge complex consists of a mausoleum and a mosque, facing each other on a raised platform.

As we entered the gates, after paying our entry and camera fee, we could get a feel of the grandeur and the largeness of this monument. A red sand path, neatly laid and lined with small pruned bushes, cut through the enormous, manicured lawn. We could make out three structures in front of us. On our left was the larger structure, the mausoleum; on our right was the mosque; and in the middle, a small squarish building with four minarets that, upon a closer look, turned out to be the entrance gate to the Rouza. This building had connecting walls, with huge arches cut into it, running on all four sides of the Rouza creating an outer wall boundary.

We passed through the small door of the entrance gate and came to a flight of stoned steps. The steps took us to the raised platform where the mosque and the mausoleum faced each other. An empty step tank with a fountain in the center lay between the two structures.

The Mausoleum at Ibrahim Rouza

The Mausoleum was built from a single rock and the architect, according to the inscriptions on a wall, was Malik Sandal. The outer wall of the mausoleum had seven arches each on all the four sides, two of them narrower than the others, creating an outer walkway. The inner aisle had pillars neatly placed for symmetry.

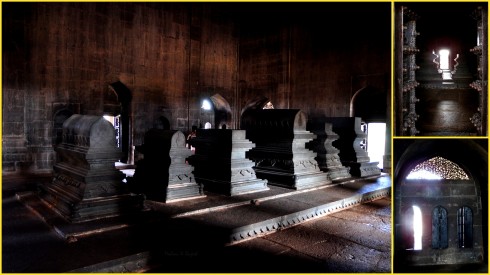

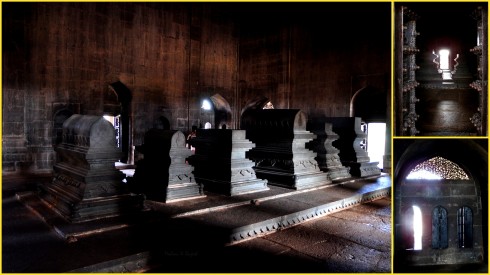

Inside the mausoleum at Ibrahim Rouza

The panels on the wall had inscriptions in Persian and other floral patterns and embellishments. The doors and windows of the tomb were made of wood and had carvings that resembled temple doors. The inner tomb chamber has six tombs that belong to Ibrahim Adil Shah II, his wife Taj Sultana, his mother, his daughter Zohra Sultana and his sons Darvesh and Sulaiman. The original remains are said to be in an underground chamber.

The tomb chamber at Ibrahim Rouza

The mosque was smaller in size and had a prayer chamber with a facade of five arches in front. The over hanging roof has four minarets at each corner, a single bulbous dome with a row of petals at its base at the center and a beautifully carved parapet. The prayer hall was lined with high arches, each with beautiful carvings.

The Mosque at Ibrahim Rouza

The place was bustling with tourists. Children in school uniforms of all imaginable colours, walking in pairs and groups alike, listening keenly to what their teachers were explaining; ladies clad in burqah with their kids tagging along; a few serious devotees oblivious of the noise around, praying silently; and a couple of foreigners, red from the blazing sun, and carrying cameras with lenses bigger than their backpacks.

Our cameras were going crazy. The monument seemed to be a perfect place for photography enthusiasts.The tombs against the skies, peppered with scattered clouds, looked out of the world and gave us some beautiful pictures.

Another view of Ibrahim Rouza

We walked back to the entry gates, ready to resume our tonga ride.

But it was already past noon and time for our lunch. Our tonga stopped in front of a vegetarian restaurant. We invited Mohammad Anwar for lunch but he declined, politely, saying that he had his own food with him.

We had at least four more hours, post-lunch, and had to cover as many number of monuments. For the time being we were exhausted, from the sun, from the ride, our stomachs were empty; but our minds were full from the continuous supply of knowledge on history, heritage and architecture. We had to rest our minds too – for a while.

The tonga ride continues….

![Kudremukh range [photo courtesy Nithin PM]](https://travellenz.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/nithin1a.jpg?w=613&h=294)