Picture an unconquerable fort built in red granite stone, guarded by a 20 feet high entry gate, enclosed in a fort wall running around the 5 mile perimeter; 101 bastions, each about 40 feet high, are cut into the fort wall; beautiful palaces with exquisite carvings; perennial springs constantly irrigating the fruit and flower gardens; old temples, providing a look into a past with their walls, pillars, ceilings and floors sporting bas reliefs, co-existing with a mosque, probably built by different rulers……….

Unconquerable because the fort is protected by a deep gorge on one side, 4 km long and 700 m deep, with enormous boulders adding to its natural defense, cut by a river flowing below.

As I stood safely on one of the flatter and non-swaying stone platforms right next to the deep gorge, Pennar River seemed harmless, a bit stagnant and definitely not flowing, at the bottom. Nothing much of the unconquerable fort remains, albeit the crumbling fort wall, we couldn’t go a few feet without seeing some sort of a ruin that lay amidst a mix of stone boulders that were scattered around the place.

Welcome to Gandikota – the Hidden Grand Canyon of India.

How many places can claim to be literally gorge-ous, other than, of course, the Grand Canyon. The scale here may be smaller, or rather minuscule, as compared to the 446 km long, 29 km wide, and 1,800 m deep gorge cut by the mighty Colarado River in the Arizona State, USA, but the setting is no less breathtaking. And it goes one notch up if you were to imagine the backdrop holding a sprawling ancient fort, a mosque, a couple of exquisitely carved temples and the history behind the area which played a significant role in some of the well known dynasties that once ruled southern India.

Gandikota Fort is situated in Gandikota, a small village situated in the Erramalai hills on the bank of the river Pennar in Kadapa district, Andhra Pradesh. Gandikota gets its name from the word ‘Gandi’ which means gorge in Telugu. The fort is believed to have been constructed during the 12th century by a subordinate of a Chalukyan king and has also served many a crucial role during the reign of the Vijayanagara, Qutub Shahi and Kakatiya dynasties.

We did not choose this remote location for our next driving holiday for nothing. And we did not choose it overnight. Gandikota had been on our travel plans for quite a long time. We’ve been curious about this place for a while as photos from other travellers kept appearing in our Google stream.

Our driving holidays always started with the car headlights on. But this time, due to a pre-planned engagement, we had to push our start time way ahead of our usual 5.00 am departure to a 10.30 am one. Being a Saturday and the beginning of the long Pongal weekend (if you had taken a day off in between), we did not expect the traffic to be smooth flowing on the outer ring road. It took almost an hour to reach the Devanahalli toll.

Our route plan was to drive through Devanahalli – Chikkaballapur – Gorantla – Kadri – Pullivendula – Jammalamadugu – Gandikota, passing many small villages like Thondur and Muddanur on the way. It was going to take us around 5 hours to cover the 250 odd kilometers.

The road was good, excellent in some stretches. We did follow the NH 7 till Gorantla, from where we took a right turn and followed the road to Kadri. We also saw the diversion to Puttaparthi ( and thought maybe some other time). The roads got a bit narrower whenever we had to pass through smaller towns and we had to clamber across the sharp bumps sometimes. We also had some difficulty cruising amidst the many pilgrims who had congregated in front of the Narasimhaswamy Temple in Kadri. Later we came to know it was Vaikunta Ekadashi, an auspicious day to visit the temple.

Once we had left the grime of the city behind, the scenery around us changed. The landscape became a breathtaking mosaic of yellow sunflower expanses, fluffy cotton fields, jowar, millet, sugarcane and rice plantations. There were patches of barren scrub lands and conical hills dotted with jagged rock faces looming in the distance. While driving through the beautiful countryside I could not stop deeply breathing in with the clean air the open roads, a welcome break from the usual traffic congested and heavily polluted cities.

While driving on the village roads a lot of things can happen. You are sometimes stuck between goats with big floppy ears passing by or you are marveled by the sight of the white egrets waiting on the paddy fields to pull out worms and looking more like guarding a cricket patch, complete with all the positions starting from first slip, second slip and so on, or you are slowed down as the road has been encroached upon by a smart farmer who thought he could use it to dry hay or his red chilly produce of the day.

We also had to pay attention to the two wheeler riders. They need to be aware of the fact that their vehicles are meant for only two people and not for the whole town. One of the common sights on the road were to see up to three or sometimes four adult passengers on a scooter. ‘And what is a helmet?’ they may ask in these places.

Other than the towering hills, some other towering machines also caught our attention. Wind mills, standing tall, casting shadows across the hills and fields, a stark juxtaposition of ancient and modern India. These wind-powered turbines set up by Suzlon Energy are here to bring a wind of change and are probably the only solution to a country plagued by power blackouts.

At Mudannur, we took a wrong turn but an elderly man guided us onto the right road. He actually told us the way till Gandikota – first we had to cross a railway line and then go straight on the Jammalamagudu Road up till a huge bridge that crosses Pennar River. Before the bridge, turn left and the road will take you straight to Gandikota. But our Google map had something else in store for us and it coaxed us to take a left turn well before the bridge only to pass through a small village. Nevertheless, the villagers did guide us through a shortcut and we did reach the Gandikota APTDC complex by 4 pm.

Covering an area of about 10 acres with 12 cottages, a dormitory, a dining hall and kitchen, and most importantly a huge parking space and kids play area, the APTDC complex at Gandikota is a sprawling affair. To match with the fort beside, the whole complex is built in stone.

I had called the APTDC Bangalore reservation office to make bookings for the stay here. ‘There are no online bookings for Gandikota, only offline bookings’, a lady at the reservation center told me. She gave me the manager’s number but also warned me that the signals were very weak there, but rooms will be available as it is a huge complex. After many tries I finally got the manager, Mr Ramanuja Reddy, on the phone, and booked a room.

It turned out that Mr Ramanuja Reddy was away for the weekend and Mr Basha the manager cum attendant cum kitchen in charge cum everything else came to our service.

The room looked cosy and spacious, though the TV and water heater were not working. After keeping our bags in the room we did not waste timing in driving to the fort which was located just a kilometer from the APTDC complex.

We parked our car just inside the entrance and walked through the huge gate. It led us onto a winding path that took us to an open area.

A whole village existed inside the complex – houses, shops and even a primary school. We followed the stone path, jumping over a few lazy cattle, cow dung and scuttling chicken. On the way, we passed several ruins. We first saw a four-tiered tower, aptly named Charminar.

We passed a brick building which was marked as a Jail. The gate was locked from outside so we could not go inside the compound. We also saw a small path on the left that led to the Madhavaraya temple.

The village road ended at the Jamia Masjid. We later came to understand that we could have taken the car further inside through the village road till the Masjid, as we found a few tourist cabs parked adjacent to the mosque’s wall.

We wanted to see the sunset from the gorge before it would get late, so without paying much attention to the ruins we made our way to it.

We passed the Masjid, a building which was marked as Granary and the Ranganatha Swamy Temple.

We had to scramble up, across and down a few huge rocks to reach the gorge.

You do not realise that there is something in store for you till you reach the very end of the chasm. If you’ve ever been here, you will know the feeling… your heart skips a few beats and you find yourself breathless as you approach the edge. A massive chasm, very wide and very deep, standing between you and the other side.

The walls of the gorge were extremely impressive. Our eyes trailed down the magnificent cliffs and rock faces. We could make out the different layers of rock by color – red, brown, grey – which proved how old these mountains were. You see billions of years stacked up and cut through. Considering how flat the drive to Gandikota was, it was hard to believe how high you really are until you reach the rim and look down into this gorge.

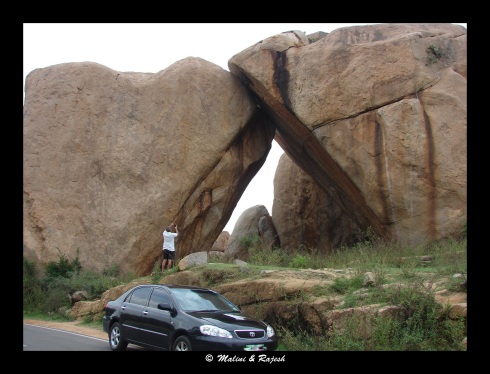

The beauty of the gorge, the different colored rocks, the huge boulders placed precariously over one another as if they were dropped from the sky and the vast expanse of the place…… it’s amazing how nature works. There were several higher rock formations standing separate from where we were standing. We were lost in a world of magical shapes that rose from the ground and which gave a surreal touch to the landscape.

We tried climbing up some of the boulders. It was a treacherous climb at some places, considering the fact that we did not know whether the stones were loose. The rocks were still warm from the scorching sun. If in January, when we visited, it was this hot, one could imagine how hot it would be in the summers.

From the top, we could also get a better view of the crumbling fort wall that snaked around the fort.

We could also get a glimpse of the Mylavaram dam and reservoir from the chasm.

Also snaking below was the Pennar river – that force that must have helped to shape this gorge – but now the river was not flowing. I had seen pictures of a more fuller Pennar, may be taken soon after the monsoons.

We realised that the sunset was actually behind us, on the opposite side of the gorge. As dusk was catching up and we didn’t want to stumble over the rocks in the dark, we thought we would climb up the nearby Ranganatha Swamy Temple and enjoy the setting sun from there.

Judging the position of the sun as it set, we mentally calculated that the sunrise would be directly over the gorge and decided to come early the next morning. And we also had to visit the temples and the mosque.

We had a simple dinner and slept early.

The next morning, watching the sun rise over the raggedy canyon was as mesmerizing as its effect it had on the ruins nearby. The rocks shimmered and shone as the sun rays fell on them. In the morning the place was a joy to behold. The babblers, thrushes and partridges were poking around for breakfast. And of course the gorge itself is a visual delight.

We realized that one cannot survey the gorge from the edge of the chasm. Maybe one should find a way through the rocks to venture inside and track down the hidden caves and tunnels once used by the soldiers to comprehend the depth of the canyon. We had read somewhere that there were a few paths to the valley through caves, one of them still used by the locals can be found near the western edge of the fort.

When the sun rose, we took in the breathtaking scenery that unfolded in front of our eyes. There was only one other group of 4-5 people who had clambered further up to the very edge, but they were more interested in testing the gorge’s echo quality feature than the rising sun.

When the echoes got unbearable and the sun got beyond the reach of our camera we decided to make our way down. On our way back we again climbed onto the Ranganatha Swamy Temple for a few shots.

The temple was very much in ruins and the main sanctum stood on an elevated platform. But the exquisite carvings had not lost their sheen.

From the Ranganatha Swamy Temple, the tower of the Madhavaraya temple and the Jamia Masjid were visible.

The Jamia Masjid was locked as was the Granary.

The Jamia Masjid looked grand even in its dilapidated condition. The granary had a vaulted roof and is now used as a tourism office. We walked around and took a few shots.

We made our way to the Madhavaraya Temple. We could see the tower of the temple from a distance, but it did take a few turns and twists to reach the temple. It looked as if it were locked from outside as a huge lock was dangling from the gate. But we found out that a smaller gate was built into the bigger one and it was not locked.

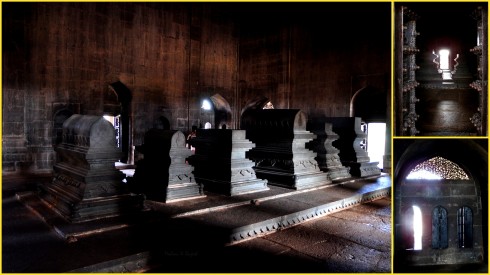

The temple was larger than the Ranganatha Swamy Temple and it did resemble the numerous Vijayanagara temples we had seen in Hampi. We entered through the towering five-tiered gopura which was also the main entrance. The huge courtyard had pillared mandapas running on all the sides.

The main sanctum was elevated and was at the center which had more pillars and a lot of intricate carvings. Other than the abundant simian population, both alive and sculpted, no other soul was in the premises.

One sculpture that caught our attention was an interesting combination of an elephant and bull. The head of both the bull and the elephant was merged skillfully, but if you would put your hand you could find that it looked like a bull from the right side and like an elephant from the left side.

Many of the stone carvings depicted stories from Ramayana and Mahabharata. We stepped inside the temple. There was no visible idol inside but a lot of bats flying inside the main sanctum. As we perambulated the temple we realized that there was another entrance at the back side which had a crumbling gopura on top.

As we walked back through the village we realized how close the villagers were living to these historical monuments, almost encroaching upon some of the structures. Are they a threat to the cultural heritage posing as a danger to this historic fort?

But don’t these residents belong to this place? This is the only social space that has been theirs for decades or may be for centuries.

Do they really understand or value the cultural heritage lying in their backyard? The banks of the Pennar were excavated long ago by Britishers and now by the ASI, only to find out that there was human habitation in the region even during Paleolithic ages.

The AP tourism should come up with plans to help the residents of the village to begin to feel ownership towards the historical monuments. We did not find any guides at the complex. And I understand that even if there were, they could only speak Telugu. But why should they bother? Only a handful of tourists drive down to reach this village and the rich heritage brings in little benefit to the villagers.

Gandikota is really an amazing place to see. The size and scale of the place, if not as huge as the Grand Canyon, is such that pictures cannot do it justice. You have to see it for yourself to really appreciate it. So go visit……