After lunch, we resumed our journey through the busy bylanes of Bijapur. It had been an eventful first half and we were getting to know this heritage city better.

On the way, Mohammad Anwar explained how difficult it was to maintain a horse with such a paltry amount they got from the tourists. A lot of his fellow tonga riders had migrated to bigger cities for better prospects only to end up on the streets doing menial jobs. “The city’s tonga population is fast dwindling with a very few left.” he said. “How many tourists do you get a day?” I asked. “You need a whole day to visit all the monuments. I hardly get to take a couple of tourists a day and make around Rs. 200 to 250. The foreigners are ready to pay more, sometimes giving me a Rs 500 note. They even offer me food or invite me to the restaurant for lunch. They enjoy tonga rides and they just love talking to the drivers. But, sometimes we are harassed by local policemen and traffic cops and we have to part with a percentage of our earnings.”

I told him about the revival of the tonga carts in Lucknow, Agra and Old Delhi and how these carts would be used to take tourists to the historical sites with guides. A smile spread on his face for the first time. “The government should start this in Bijapur too. Madame, why don’t you write to someone about this.” I nodded my head. I did not know what else to do. Mohammad Anwar smiled again, his eyes fixed on the road. I knew his mind was elsewhere. Dreaming about that White Kurta and Lucknowi Jooti.

We got down near a board that said ‘Malik-e-Maidan’.

‘The Monarch of the Plains’ was no ordinary ruler. An Iron Man – this was the largest medieval cannon (whatever that means) in the world. According to the ASI board, about 4 m long, 1.5 m in diameter and weighing 55 tons, this canon was brought back from Ahmadnagar by Muhammad Adil Shah as a war trophy. It took 400 oxen, 10 elephants and thousands of soldiers to get the beast to Bijapur.

The canon was perched on a small tower, called the Sherzi-Buruz or the Lion Tower, named after the two lion sculptures carved at the entrance. We climbed a sprial staircase to reach the canon.

And there it lay, gleaming in the sun. The canon was an alloy of copper, iron and tin. The muzzle looked like the mouth of a tiger with open jaws with an elephant on both sides crushed by its sharp teeth. It is said that the sound from the canon was so deafening that the gunners would submerge their heads in water before firing.

The canon had a few inscriptions in Persian or Arabic embossed on to the surface. Not to mention the numerous people who had taken effort to deface this national treasure by carving in their names and even postal addresses. What a shame!! And it is said that if you touch the gun and make a wish, it will come true! But the poor canon had a heavy price to pay.

If this canon had found its way to the Crimson Drawing room in Windsor Castle in England with a “Presented by the Adil Shahi Emperor” tag, would it have been treated so shabbily? Yes, my friends, the British had planned to heave this canon to England, but dropped it for obvious reasons.

It was time for our next destination – the Uppali Burz. Built as a watch tower this 25 m high tower is reached by a winding flight of stone steps. We started climbing the steps amongst hordes of giggling school girls who were finding it difficult to control their skirts flying in the winds.

It was very windy at the top, but the view at the summit was breathtaking. You could make out most of the monuments of Bijapur from here. At the top of the tower, two long canons lay.

Our next sight seeing option was Bara Kaman.

Bara Kaman is the unfinished mausoleum of Ali Adil Shah II. The monarch had wished to build a mausoleum for himself that would be one of the best in planning and architecture. As per his plan, twelve arches were to be placed vertically and twelve horizontally surrounding his own tomb, thus giving the name Bara Kaman – 12 arches. The mausoleum was left incomplete with only a few vertical arches raised, however, twelve arches placed horizontally were completed.

The story is that Ali Adil Shah was murdered by his father Ibrahim Adil Shah to prevent him from constructing this magnificent structure. Ibrahim Adil Shah feared that Bara kaman would surpass the popularity of his Gol Gumbaaz. If completed, the shadow of the Bara Kaman would have fallen on Gol Gumbaaz.

Nobody knows who the architect was but some records point to Malik Sandal, who had built the Ibrahim Rouza. To build the arches he had used an innovative technique. He had built solid walls in the shape of an arch and then had the inner part toppled so that the outer arch remained. Some of the walls were found intact to prove this point.

The Bara Kaman looked unlike any monument we had seen. It looked more like the ruins of a Tudor church, only the tombs gave an indication that this was a mausoleum. We walked among the arches, taking photos of one meeting another at the corners. A single intact tomb had been raised on a platform and the rest were on ground level, some of them in ruins.

It was time for our final stop, the Gol Gumbaaz.

Gol Gumbaaz or the round dome, the mausoleum of Mohammad Adil Shah II, is a masterpiece of Islamic architecture and synonymous with Bijapur. Known as one of the largest domes in the world, Gol Gumbaaz is also unique in the fact that the dome is not supported by any pillars.

It was the last stop in our ride around Bijapur and also time to bid farewell to our excellent guide cum charioteer. Though we requested him to pose for a snap, he excused himself and suggested we click his horse instead.

The second largest dome in the world now stood before us. We still had a couple of hours for our train back and intended to make the most of it at the Gol Gumbaaz.

The complex was brimming with tourists. Probably this was everybody’s last stop on their itinerary. Right in front stood the Gol Gumbaaz in all its grandeur. The monument was partially hidden by a two-storied building with tall windows in the shape of arches. This was the Archaeological museum; we decided to gave it a skip seeing the serpentine queues. School children were jostling against each other to get inside the museum.

We followed a blue board that said ‘Way to Gol Gumbaaz’, rounded the museum and reached a single storey building. Passing through it we got our first unobstructed view of the Gol Gumbaaz.

This was one of that occasions when you wished you had a ‘wider’ angle lens. Sometimes your lens just doesn’t want to go back, far enough. But with glass that starts at 17 mm, we should not be complaining.

The massive brick dome is supported, as earlier mentioned – not by pillars, but by a system of eight intersecting arches that create an interlocking system that bears the load of the dome. This system of interlocking pendentives is not commonly found in India. On all the four sides of the monument were seven storied towers with arched windows. These towers held the spiral staircases one had to climb to reach the top. Now only two remain open, one for the climb up and the other for the climb down.

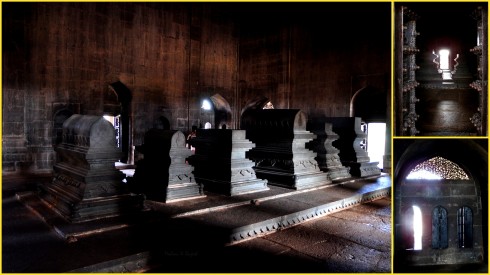

We entered the monument and checked out the tomb first. On a platform at the centre of the dome chamber lie the tombstones of Mohammad Adil Shah, his two wives, his son, his daughter and his mistress. The monarch’s tomb was covered by an ornamental wooden stand.

Their real graves lie in a chamber under the gallery. And thank God for that!! For all these centuries, these resting souls have had to endure something very horrendous that would probably be waking them up from their deep slumbers. For the Gol Gumbaaz is more famous for its “Whispering Gallery” which has now turned into a “Screaming Gallery”.

As we looked up to see from where the sounds or rather screeches were coming, we could see the rim of the gallery, near the ceiling of the dome, and people looking down, resembling a few ants on the wall.

We lined up behind a group of students for the hard climb up the seven stories to the whispering gallery. The stairs were narrow, spiral dark and claustrophobic. With every passing floor, we could hear the noise from up above rise. At first, it began as a distant drone but by the time we had heaved ourselves to the top, it was a blaring roar that seemed to echo itself many times over. Ten times over – to be precise.

Because of the dome’s remarkable acoustic properties, the faintest sound made at one end of the gallery can be clearly heard at the other end. Every sound echoes 10 times and reverberates for 26 seconds, the longest known reverberation count for any building.

We stepped out from the dark stair case and found ourselves on the roof of the monument and at the base of the dome. The view from the top was magnificent and a bit scary too – if you are afraid of heights.

The cacophony was getting louder and as we stepped into the dome it seemed as if the whole world was trying to prove a point – that every sound echoes 10 times. We heard all kinds of sounds we had never dreamt of hearing. Sreams, screeches, whistles, claps, hoots, growls, roars, monkey noises – I wonder how the emperor and his family are resting in peace.

The look down from the gallery is not for the faint-hearted. The wall of the gallery was dangerously low and as we looked down at the entrance of the gallery from where we had started our climb, the people near the tomb chamber seemed liked ants, again.

The guard at the entrance said the best time to visit the gallery was during the early hours in the morning. We promised ourselves that we would stay in Bijapur the next time and experience the “Whispering Gallery”.

It was time for our journey back.

Bijapur was a revelation. A treasure trove for those who love history, architecture, heritage and symmetry. There were a few monuments we had to give a miss. Gagan Mahal, Asar Mahal, Saat Kabar, Jal Manzil, and many more. But there is always a next time.

As we started our walk from the Gol Gumbaaz to the railway station, we scanned the roads for Mohammad Anwar, our companion for the past few hours. He was nowhere to be found. But there were others, some waiting for their customers, others trying to look for a prospective one.

But we decided to walk anyway. The tonga ride had to wait till another visit.